lock 25 (1835)

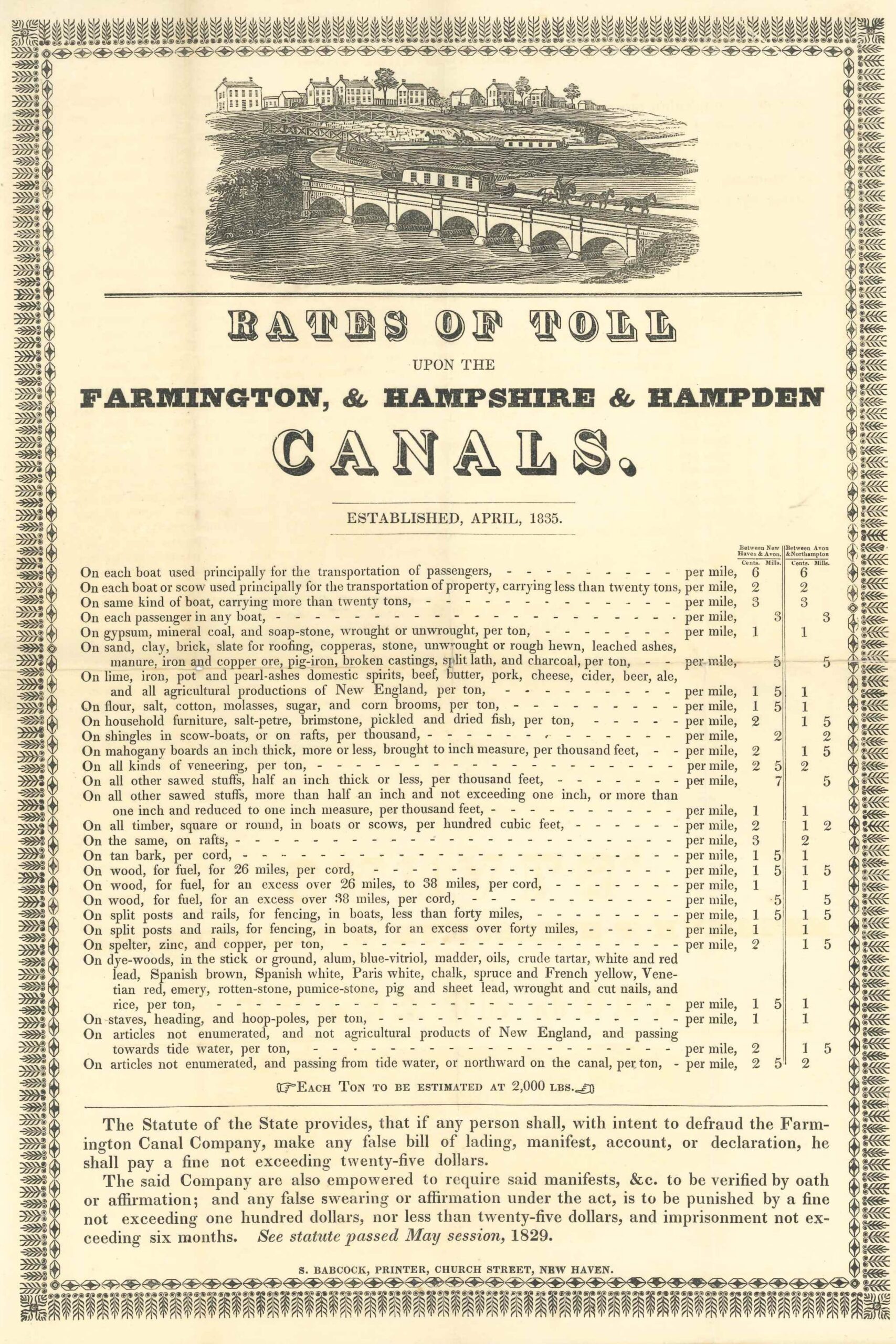

In 1835, the Farmington Canal linked up with the Hampshire and Hampden Canal in Massachusetts to allow passengers to travel all the way to Northampton, MA (84 miles) by boat for the steep price of $3.75 -- about $113 in today’s dollars. It was a 24-hour journey, and a sleeping compartment was included. But passenger travel was no longer the primary use of the canal: beginning in 1829, goods and raw materials -- flour, meat, rice, tea, lumber, coal, stone, ore, and more -- were transported up and down the canal in cargo boats.

With no engines or sails, most of these small boats -- passenger and cargo both -- needed to be towed along by horses or mules. The Farmington Canal, like all canals of its day, had a towpath running alongside it where the draft animals would walk, pulling their boats along with a rope. In 1835, the canal started to allow small steamships as well, which could move along under their own power but ran a higher risk of causing damage to the canal itself. By the latter half of the 1830s, more than a hundred cargo boats would travel the canal each month, transporting millions of pounds of goods.

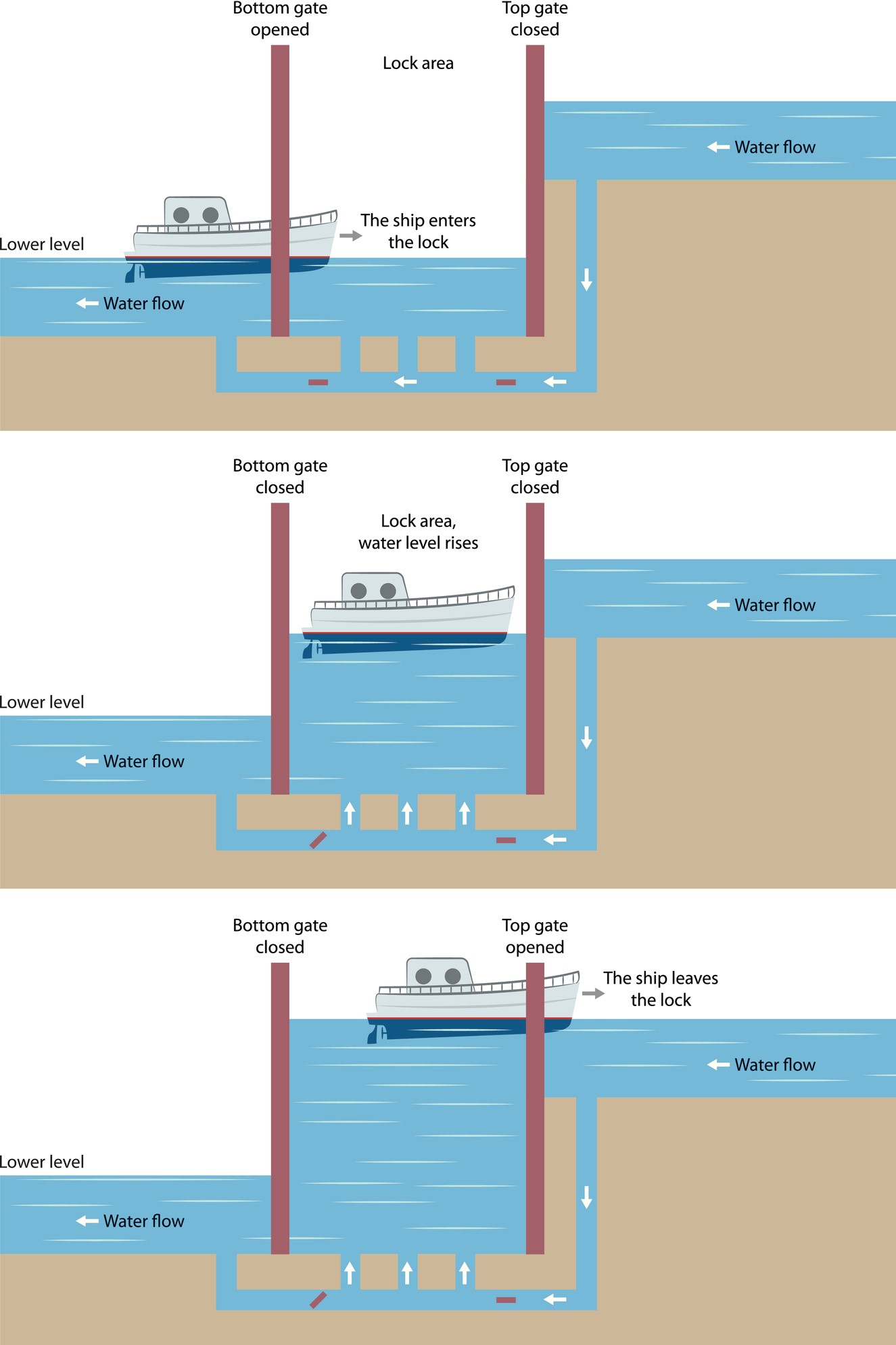

There was a 292-foot elevation change along the route of the canal between New Haven in the south and Granby in the north, but canal traffic requires a level, placid body of water -- not a rushing river. So each section of the canal was kept as flat as possible, and elevation changes along the route were handled by locks, which acted as “boat elevators,” raising or lowering boats between canal sections at different elevations. On the Connecticut section of the Farmington Canal, there were 28 locks, and each one could raise or lower a boat as much as 9 feet. Each lock was operated by a lock keeper. In New Haven, the lock keepers were mostly farmers whose lands abutted the canal; they would come running to operate the lock when a passing boat rang its bell, and were paid a small fee for their service.